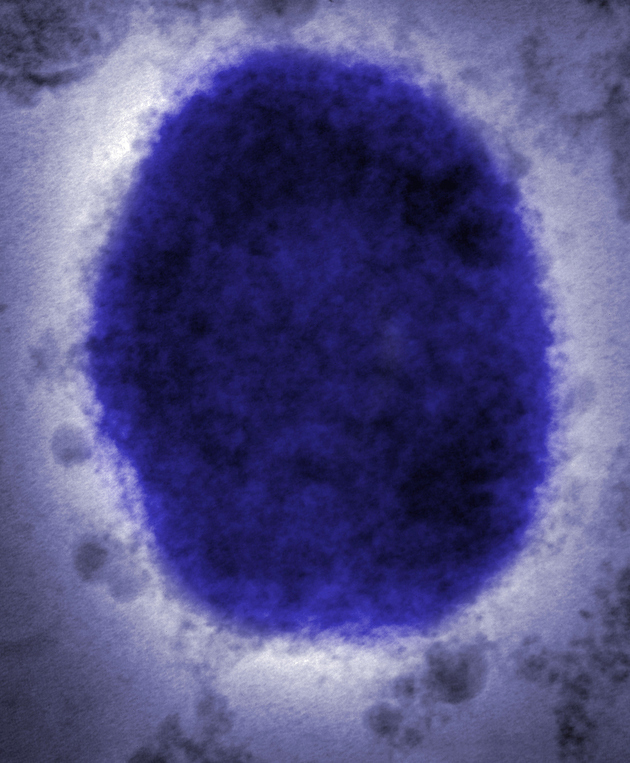

Photo/VCG

With Israel, Switzerland and Austria becoming the latest countries to confirm cases of monkeypox, the total number of nations reporting outbreaks reaches 15, according to news reports. The World Health Organization (WHO) cautioned on May 21 that more cases may be found in those countries and beyond.

As of 21 May, 92 laboratory-confirmed cases, and 28 suspected cases of monkeypox with investigations ongoing, have been reported to WHO from 12 Member States that are not endemic for monkeypox virus, across three WHO regions. No associated deaths have been reported to date, according to a WHO report.

On May 20, the WHO convened a meeting of experts and technical advisory groups to share information on the disease and response strategies.

There are still many unknowns about the transmission mode, clinical characteristics and epidemiology of monkeypox, said WHO Assistant Director-General for Emergency Response Ibrahima Sousse Faller.

Monkeypox is a viral zoonotic disease. Monkeypox virus can be transmitted from animals to humans through close contact, according to Xinhua News Agency. Although human-to-human transmission is not easy, people can also be infected by close contact with the infected ones.

Symptoms of monkeypox infection mainly include fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, swollen lymph nodes, chills and fatigue, and usually a rash which commonly starts on the face and then spreads to other parts of the body. Most infected people recover within a few weeks, but some become seriously ill and even die.

How is this monkeypox outbreak different from previous ones in human history? Is there a fatal danger? Is it related to Covid-19? Is there evidence that the monkeypox virus is circulating in communities? What precautions should the public take?

Bearing those questions in mind, National Business Daily (NBD) had the dialogues with Daniel Bausch, professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and Prof Neil A Mabbott, Personal Chair in Immunopathology, and Director of Teaching at The Roslin Institute & Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Sciences, University of Edinburgh.

Professor Bausch is also the UK representative on the WHO Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network Steering Committee and has previously held senior positions at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as the United Nations, the National Institutes of Health, the National Academy of Medicine and the Agency for International Development. Professor Bausch specializes in the research and control of emerging tropical viruses, with over 25 years' experience in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia combating viruses such as Ebola, Marburg, Lassa, hantavirus, and SARS coronavirus.

Monkeypox virus Photo/VCG

NBD: We know that this is not the first time the monkeypox virus was discovered in human history. How does the recently-confirmed monkeypox virus differ from the previous ones?

Daniel Bausch: Monkeypox is endemic in the West and Central Africa, where it is maintained in nature in certain types of small mammals, i.e. rodents. Sporadic cases were reported primarily from Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There are probably more, but surveillance is incomplete.

What is unusual about the current situation is that, first, we simultaneously have confirmed cases in numerous countries on two continents, and second, we do not yet have a clear understanding of how these people got infected. There is no clear link to travel to Africa (most or all the cases did not travel there) nor an obvious link to exported animals. But it is still at early stages, so (we are) still trying to put the puzzle together.

NBD: For the monkeypox cases that have recently been identified in countries like the U.S., the UK and Spain, how deadly are they? Could the recently-confirmed monkeypox virus develop to become more deadly? Does it pose risks to the public?

Daniel Bausch: There are two different strains, called "clades", of monkeypox virus, one that circulates in Central Africa and another in West Africa. The Central African one is more dangerous, with a case fatality rate of around 10%. The case fatality of the West African clade is around 1%.

There is no reason to believe that these viruses would somehow become more deadly or fundamentally change their biology. The risk to the general public is extremely low and there is certainly no cause for panic. Although of course, we need to get to the bottom of this and understand what is going on, it is extremely unlikely that we will have a large outbreak or pandemic of monkeypox.

Neil A Mabbott: The general public should not panic as the risk to the population remains low. This isn't going to cause an epidemic in the same way that COVID-19 has. This is because the monkeypox virus doesn't spread easily between people, and very close contact with an infected person is required for the disease to transmit.

In the majority of people, the disease the virus causes is usually mild and self-limiting with recovery in a few weeks. However, in some individuals, the infection can be lethal. The mortality incidence after infection with the West African strain of monkeypox virus is estimated to be approximately 1%, but this may be much lower in countries with well-resourced health care services.

NBD: As far as you know, does the recently-confirmed monkeypox virus have anything to do with COVID-19?

Daniel Bausch: No connection. It is worth mentioning, however, that this underscores the need for effective global surveillance systems for the early detection of infectious diseases. The fact that these cases are being detected is a credit to that system, but still more needs to be done. A disease like monkeypox is easier to detect because of the typical rash that is relatively easy to spot. In contrast, respiratory diseases like COVID-19 are much more difficult to distinguish and rapidly differentiate from the many other pathogens that cause respiratory illness.

Neil A Mabbott: No, the monkeypox virus is very different to the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. The occurrence of monkeypox cases in humans in countries where the virus isn't normally present is usually associated with the arrival of travellers from an infected region. Occasionally, the disease then spreads to close family members or health care workers through very close contact with the infected individual.

Of course, the increase in international travel following the relaxation of the COVID-19 restrictions may indirectly have increased travel to and from parts of the west and central Africa where the monkeypox virus is present in wildlife.

NBD: In your view, at this stage, is there sufficient evidence that the monkeypox virus is/ has been transmitted in communities through close contact? Should people be vigilant?

Daniel Bausch: Monkeypox virus can be transmitted between humans from direct contact with the lesions (or from, for example, clothes or bedding that the person has used) and from respiratory droplets, but it is not easily contracted. It usually takes prolonged exposure.

Of course, people should always be vigilant but, again, there is no cause for panic. The risk to the average person is extremely low unless they have had close contact with a person who has the disease, or potentially travelled to Africa and had potential exposure to rodents and their excreta in rural settings. Note that the rodents that carry the monkeypox virus are not the ones you typically find in large cities. Rather, they are more rural rustic settings, so it's people out in villages, forests, mines, etc. which are not common exposures for the average traveller.

Neil A Mabbott: The monkeypox virus doesn't spread easily between humans. Very close contact with a person infected with monkeypox is required for the disease to spread. Infection can occur through the exposure of large respiratory droplets, broken skin, contact with monkeypox skin blisters or scabs, or even contaminated bedding.

NBD: What protective measures should health authorities advise people to take?

Daniel Bausch: The average person need not worry unless they have contact with someone with a rash and other symptoms consistent with monkeypox (very rare) or have been travelling and had exposures in endemic areas, as described above. No specific measures are advised other than that. For people who think they might have or been exposed to monkeypox, they should maintain themselves in isolation and contact health authorities immediately for further guidance, including laboratory testing (generally done on fluid or scrapings from the lesions), and appropriate care if sick.

Healthcare workers should use appropriate infection prevention and control practices, with personal protective equipment similar to that used for COVID-19. Vaccination with a smallpox vaccine that also protects against monkeypox may be indicated for high-risk contacts, but not for the general population.

Neil A Mabbott: You are extremely unlikely to have or be infected with monkeypox if you haven't been in very close contact with an infected person or haven't recently travelled to the west or central Africa. However, it is important that health authorities remain vigilant to detect infected cases and their close contacts so that transmission to others can be prevented.

Symptoms appearing on the skin surface of the patients with monkeypox

Photo/screenshot from the UK Health Security Agency

Extended Reading:

The UK Health Security Agency said Friday on social media that it had detected 11 new cases of monkeypox in England, taking the total number of confirmed cases in the country to 20.

Historically, cases of monkeypox have typically been reported from West Africa or Central Africa., said Jennifer McQuiston of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "We have a level of scientific concern about what we're seeing because this is a very unusual situation. And the number of cases that are being reported in the US and Europe is definitely outside the level of normal for what we would see."

In fact, the "monkeypox" virus is not a virus completely unknown to humans.

Monkeypox is a viral disease that occurs mostly in central and western Africa. It is called monkeypox because it was first identified in laboratory monkeys. But the main carriers of the virus are actually rodents such as squirrels and mice. The only significant American outbreak occurred in 2003, when a shipment of Ghanaian rodents spread the virus to prairie dogs in Illinois, which were sold as pets and infected up to 47 people, none fatally. Just last year, two travellers independently carried the virus to the U.S. from Nigeria but infected no one else.

NBD noticed that since September 2017, Nigeria has continued to report cases of monkeypox. From September 2017 to 30 April 2022, a total of 558 suspected cases have been reported from 32 states in the country. Of these, 241 were confirmed cases, and among these, there were eight deaths recorded (Case Fatality Ratio: 3.3%). From 1 January to 30 April 2022, 46 suspected cases have been reported of which 15 were confirmed from seven states. No death has been recorded in 2022.

Although vaccines and specific therapies have been approved to treat monkeypox, they are not widely used. Historically, vaccination against smallpox was demonstrated through several observational studies to be about 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. British authorities said they have offered a smallpox vaccine to some healthcare workers and others who may have been exposed.

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号