Imagine you were standing on the savannah in Africa, and a gray rhino was walking slowly not far away. In normal cases, you should walk away immediately but you didn't. The cumbersome and slow-moving creature suddenly rushed towards you and tried to knock you over. When you realized the risks, it was far too late to take actions.

US economist Michele Wucker coined the term "gray rhino" to draw attention to the obvious risks that are neglected despite, and developed it in her eponymous 2016 book. The concept quickly attracted worldwide attention, but gained greater popularity in China than in Europe and the US. Entirely different answers of the regions to risks drove Ms. Wucker to investigate cultural and regional differences and personal experience in the sequel You Are What You Risk.

In the era replete with uncertainties, risks are everywhere, and everyone has a personalized "risk fingerprint" that describes what kind of risk-taker they are. So what is the relationship between risks and individuals or companies or decision makers? What should people do to improve risk management? In an exclusive interview with National Business Daily (NBD), Ms. Wucker shared her original insights on the dynamics behind the relationship.

Michele Wucker (Photo provided by the interviewee to NBD)

Risk fingerprints explain the way people respond

NBD: The concept of "gray rhino" has provided an important theoretical framework for decision makers all around the world to recognize and prevent risks. What prompted you to think about it and brought in the concept of "gray rhino"?

Wucker: The "gray rhino" was inspired by the difference between the Argentine and Greek debt crises. Both countries in effect saw a big dangerous beast coming at them, and only one acted in time. I wanted to explore why. I knew the question was much bigger than just two sovereign debt crises, so wanted to do so in an accessible way.

Throughout history, humans have used animal stories to help us to put the world in context. The rhino made sense: big, dangerous, with a giant horn. The color gray reflected how surprisingly likely we are to mis-characterize the obvious. It comes from the fact that all rhinos are gray, but two of the five remaining species are called "black" and "white" even though neither is the color of its name.

NBD: Your book The Gray Rhino made a great hit in China. What do you think has made it so successful?

Wucker: The answer that made the most sense to me was "You gave us a way to talk about something that was on our mind." That same question is part of what led me to investigate cultural and regional differences in "You Are What You Risk", and what I found was fascinating.

Risk sensitivities and preferences vary widely across countries and regions. This includes the kinds of risks people think about and how inclined they are to worry, how accurate their risk perceptions are, and how much confidence they have in individuals’, organizations’, governments’, and international organizations’ ability to protect them from risks. Some research suggests that Asian countries are more sensitive to risks than Westerners are.

On artificial intelligence, for example, Asian experts believe that machines’ capabilities will overtake humans’ much faster than Westerners do. Other research shows different risk perceptions and behaviors in cultures with collectivist versus individualist values. There is a relationship between belief in the ability to affect an outcome and how much attention is paid to a risk.

NBD: A new concept called "risk fingerprint" was put forward. Could you explain it to us?

Wucker: The risk fingerprint concept is very useful as a complement to the five stages of a "gray rhino" event. Using "gray rhino" theory, I work with groups to map where various stakeholders are in the five stages of responding to a "gray rhino" and to use those insights to develop better responses. Risk fingerprints help to explain why they respond the way they do and thus to inform strategies that can motivate and move different people and groups from denial to action.

It's right to communicate "gray rhinos" challenges publicly

NBD: The US Treasury Secretary recently stated that the US is likely to trigger a historic financial crisis in October due to debt default. At the same time, even after seeing what China did to control the Covid-19, the US still lacks effective measures to fight the pandemic. What are the reasons behind?

Wucker: Political dysfunctions brought the US dangerously close to letting a completely preventable crisis happen. This is not the first time that the debt ceiling has become a political football and threatened the creditworthiness of the United States.

With COVID-19, the United States’ initial response was terrible, and we still have problems. We were very slow to respond. Worse, many citizens refused to act responsibly. We do deserve credit for developing vaccines quickly. Despite that, our vaccination rates are much lower than they should be because some people refuse to get their shots, often for political reasons.

A recent Pew Research study said that the US was more politically polarized in its COVID-19 responses than any of the other countries in the study.

Both examples are the result of the US facing a meta "gray rhino", that is, problems with governance, political polarization and tribalism, and misinformation make it hard to address the other very serious challenges we face.

NBD: What's your opinion on China's reaction and action to "gray rhinos" in recent years?

Wucker: China is right to publicly recognize its "gray rhino" financial risk challenges in liquidity, credit, shadow banking, capital market shocks, insurance, and real estate bubbles. These are complex issues that are very, very hard to solve.

The financial issues China has identified are especially difficult because they are so interconnected, and measures to fix one issue can have unwanted side effects. Every decision involves trade-offs. And it is never easy to execute policies that involve short-term pain even though that means the total amount of pain will be less.

But the thing about financial bubbles is that the longer policy makers wait to deal with them, the bigger the pain will be. So China is right to act sooner rather than later, and right to communicate publicly about the problems that the economic team is trying to address and acknowledge that they are big challenges.

NBD: At present, the aging problem is getting more and more serious globally. What’s your view on this issue? In your opinion, for policy makers, how can they better encourage childbirth?

Wucker: Aging represents some very real "gray rhinos" including the falling number of young workers supporting more older workers, the need for medical care and housing, the fall in consumption, the question of whether pensions are adequate. But aging is closely related to other "gray rhinos": worries about automation and artificial intelligence replacing some human jobs; questions of whether our planet can sustain humanity if we continue to behave and expend resources the way we are.

Encouraging people to have more babies might help with the young to old worker ratio or total GDP, but then you run up against problems of whether the jobs will be there or how the planet can support them.

So there need to be other solutions. For example, can the economy be structured so that the older population draws more support from rising productivity because of technology and less from future workers? Can policy makers increase GDP per capita instead of total GDP? Can we apply new technologies and change lifestyles so that the impact on the planet of each person is smaller?

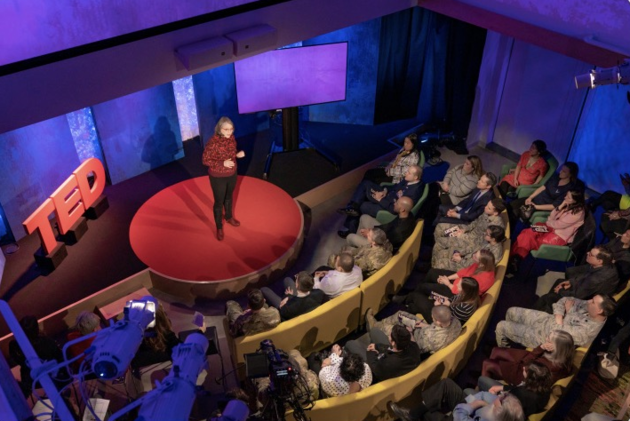

Ms. Wucker was giving a speech on TED's stage (Photo provided by the interviewee to NBD)

Risk literacy should be more holistic

NBD: In the new sequel, you analyzed the influence of personal personality on risk appetite. Do you think individuals can make decisions that differ from their own personalities when they dealing with "gray rhino" incidents?

Wucker: Just like the arches, whorls, and loops in your fingerprint, your innate personality is pre-determined and not something you can change. But that innate personality interacts with your experiences to create new feelings and behaviors. And, in turn, you can build habits and optimize your environment to make the best risk decisions. This only works if you are self-aware of these dynamics.

I get asked a lot if there is an "ideal" risk personality. I think it's so important to put yourself in situations where you can take risk decisions that are best suited to your personality and skills.

NBD: Individuals will inevitably encounter some "gray rhinos" in daily life. Taking career and marriage as examples, how can individuals build a preventing system for "gray rhinos"?

Wucker: Everything starts with self-awareness: thinking about what makes you comfortable or sets off alarm bells, and why you tend to respond the way you do and end up in denial or act in face of a "gray rhino". If you know you are likely to leap before you look, make sure you turn to friends who are more cautious and seek their guidance. If you are fearful about taking chances –even for good things—look for a supportive group of people.

Then you can set up habits, like regularly asking yourself what the biggest "gray rhinos" are in your career or relationship. Then evaluate how well you are doing in responding and what you might change to do better.

NBD: Great individual risk awareness against "gray rhinos" is inseparable from a solid public education system. How to improve our public risk literacy?

Wucker: Each one of us is unique and risk management is a skill every one of us needs in our own life. Risk literacy should be more holistic, involving human, emotional elements and recognizing the difference between subjective and objective risks.

Teaching creativity is very important, as is encouraging critical thinking not just rote memorization. These are related to each other. Adults often try to re-create risks by going on outdoor adventures and challenges, this type of experience can be helpful for children as well.

NBD: Abilities to deal with risk differ from people to people. Someone may foresee the "gray rhino" incidents, but they are unable to change or prevent the risk. What is your view on this? Do you have any practical advice for them?

Wucker: Often the reason people do nothing in face of a "gray rhino" is because they feel they have no power to affect it, or because they feel it's someone else's responsibility. This is dangerous, particularly in a situation like a pandemic when to defeat the virus we need everyone to do everything they can, or with climate change where the solution has to involve everyone.

That’s why in risk communications it is important to let people know that there are simple, effective things they can easily do that can make a difference. This includes wearing masks and getting vaccines and encouraging people you know to do so; or being careful about how much energy you use.

If you cannot do anything to prevent something bad from happening, then you just have to focus on how you can get out of the way.

Economics helps with decision-making

NBD: In retrospect your personal upbringing, what drove you to embark on the path of economics research? What is the charm of economics for you? What do you think is the value of economics for people's daily life?

Wucker: Economics is so important for understanding how the world works and for making good decisions. I first became interested in economics in high school in the 1980s reading about the developing country debt crisis, though I didn't pursue it in greater depth until much later. After college, I lived in the Dominican Republic where I was struck by the economic realities of a poor country. So when I got to graduate school at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs in 1991, I took a lot of courses on political economy and finance.

On a personal level, my mother and father come from very different upbringings when it comes to risk and uncertainty. My dad's parents responded to the past uncertainty by working hard to create a very organized life, including extremely detailed plans for their funerals well before they died. My mom's mother took a very different approach, making it very difficult for her children to deal with her affairs after she died. So you could say that I grew up with conflicting messages and attitudes toward risk and dealing with things or not. I suspect that's why risk and response have become my obsession.

Email: gaohan@nbd.com.cn

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号