Photo/Zhou You (NBD)

On March 13, 2024, the European Parliament officially approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA), making it the first comprehensive AI regulation in the world. The AIA is a landmark legislation that will have far-reaching implications for the development and use of AI technologies around the globe.

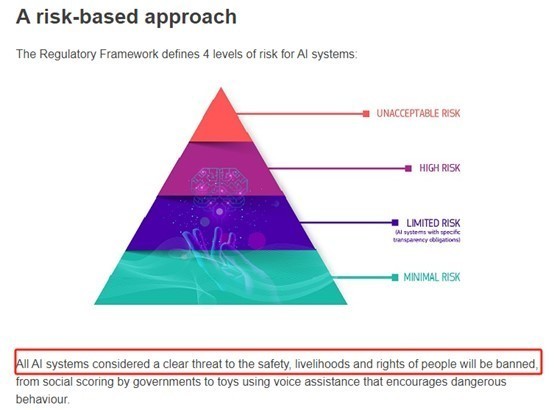

NBD noted that the EU’s “Artificial Intelligence Act,” which originated in 2021, will regulate AI technology based on the level of risk.

After the act was approved, how generative tools like ChatGPT will be regulated gained worldwide attention. It is said that generative models will be included in the general AI models, and regulated based on whether there is a “systemic risk”, which could pose challenges for supervision of large language models.

Regarding the impact of the act itself on global AI regulation, Steven Farmer, a partner and AI expert at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, one of the world’s top law firms, said in an interview with NBD, “I believe the EU’s AI Act is very likely to become a template for the world. This is a key moment in the global race to regulate AI.” He explained that the EU has already set the direction for global progress in AI regulation, citing the EU’s “General Data Protection Regulation” as an example.

How will tools like ChatGPT be affected?

It noted that the Act should ensure that AI providers consider the impact of their applications on society at large, not just the individual.

According to the EU website, AI systems that can be used in different applications are analysed and classified based on the risk they pose to users. NBD found that The EU AI Act classifies AI systems into four different risk levels: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal risk. According to the functions and impact of AI systems, the act prohibits eight types of AI applications.

Photo/EU

Then how will generative AI tools like ChatGPT be regulated?

According to foreign media reports, the act only mentions “generative models” twice and includes these systems into the so-called “general AI (GPAI) models.” Depending on whether these models pose a “systemic risk,” they may be subject to different requirements.

Charles-Albert Helleputte, head of EU data privacy, cybersecurity, and digital assets at the global law firm Squire Patton Boggs, said, “You also have that intermediary category [the specific transparency risks] where for the LLMs, they had to do something and put an additional layer. It’s not exactly high risk, but it’s kind of in the middle … the addition of a new category that sits in the middle of high risk and low risk will lead to thousands of difficulties in the implementation, the enforcement is different, the rules are different”. “It’s going to be tricky.”

According to reports from technology law media, questions around where the liability would fall between the providers and users of AI services have been lingering ever since the first legal complaints were raised against generative AI tools. On Wednesday, the act gave a clear answer: liability falls on both. Although AI system providers or developers bear most of the compliance requirements, how users or deployers utilize these tools will determine the type of responsibility they face.

“[The EU AI Act] has indicated that if there's enough significant change that the deployer has made to the development of the platform, that they then become both developer and deployer,” said Ashley Casovan, managing director of the International Association of Privacy Professionals' AI Governance Center.

However, Helleputte believes that distinguishing between the responsibilities of developers and users may be difficult, “When we look at the divergence of responsibilities between developers and users, you will find that there is a transfer of responsibility between one party and another… the boundaries may not be so clear.”

According to the EU, The AI Act will enter into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal, and will be fully applicable 2 years later, with some exceptions: prohibitions will take effect after six months, the governance rules and the obligations for general-purpose AI models become applicable after 12 months and the rules for AI systems - embedded into regulated products - will apply after 36 months.

Violations of the AI Act could draw fines of up to 35 million euros ($38 million), or 7% of a company's global revenue. This isn't Brussels' last word on AI rules, said Italian lawmaker Brando Benifei, co-leader of Parliament's work on the law.

Top Law Firms: AI Act Expected to Become “Template”

Legal professionals say that the act is an important milestone in international law for AI regulation, which may pave the way for other countries to follow suit.

Steven Farmer, a partner and AI expert at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, one of the world’s top law firms, said in an interview with NBD,“I think there is a very real possibility that the EU’s AI Act becomes the world’s template, and the vote is therefore a critical moment in the global race to regulate AI. The mood on the ground certainly seems to be that the EU has set the global direction of travel.”

Some foreign media mentioned that one of the biggest challenges for this act is whether whether the EU's upcoming regulation for AI will diffuse globally, producing a so-called “Brussels Effect”.

Steven Farmer mentioned to NBD an important precedent for the EU in data regulation: the “General Data Protection Regulation” (GDPR) enacted in 2016. Within two years after the regulation was published, global technology giants such as Meta and Microsoft updated their services.

“We also saw the EU move first in the rush to regulate data, giving us the GDPR, which we are seeing a global convergence towards. The AI Act seems to be a case of history repeating itself.,” Farmer said to NBD.

In fact, the passage of the AI Act faced many controversies. As talks reached the final stretch last year, the French and German governments pushed back against some of the strictest ideas for regulating generative AI, arguing that the rules will hurt European startups.

Cecilia Bonefeld-Dahl, Director-General of the European technology industry organization Digital Europe, once said "We have a deal, but at what cost? We fully supported a risk-based approach based on the uses of AI, not the technology itself, but the last-minute attempt to regulate foundation models has turned this on its head."

“Concerns have been raised about whether the Act stifles innovation, but in reality I think the Act sets some safe parameters for innovations. Looking at the list of banned uses of AI, I really can’t see these being objectionable. “ said Farmer, "There has been debate about whether the EU has successfully moved first or moved too soon. What we’ve been given is a very comprehensive framework that I think balances safety and innovation. The EU will probably enjoy first-mover advantage as other states look to develop similar measures."

While the EU’s AI Act is the first of its kind globally, the EU is not alone in its efforts to regulate AI technology. Last year, the United States signed a comprehensive executive order on AI, and legislators in at least seven states are in the process of drafting their own AI legislation. Additionally, other countries and regions, including China, Japan, and Brazil, as well as international organizations like the United Nations and the G7, are also working on establishing AI regulatory frameworks.

However, Emma Wright, partner at law firm Harbottle & Lewis, raised concerns that the act could quickly become outdated as the fast-moving technology continues to evolve.

“Considering the pace of change in the technology — as shown with the launch of generative AI last year — a further complication could be that the EU AI Act quickly becomes outdated especially considering the timeframes for implementation,” she said.

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号