Andy Palmer Photo/Provided to NBD

Andy Palmer, when he was serving as the Chief Operating Officer of Nissan, played a key role in developing the world's first mass-produced electric vehicle, the Nissan Leaf. For this achievement, he earned the nickname, "Godfather of EVs".

He also served as the CEO of Aston Martin, leading the century-old brand through its electrification transformation.

Recently, Andy Palmer have an exclusive interview with National Business Daily (NBD).

When discussing the booming electric vehicle market in China, Palmer stated that it was a well-planned "overtaking" strategy, and the Chinese experience was a key factor that inspired him to develop electric vehicles.

He also told NBD that in the future, robotaxi will challenge the traditional private car model.

When asked about Donald Trump's plan to impose tariffs on cars imported to the U.S., Palmer commented that tariff protection was a big mistake, as it would make the industry less competitive, and protected companies would grow weaker over time.

On Robotaxi and Autonomous Driving: A Challenge to Private Car Ownership Models, and Software and AI will be New "Engines"

NBD: The industry is currently chasing autonomous driving taxis (Robotaxi) and autonomous driving technologies. What are your thoughts on this?

Palmer: Robotaxis will no doubt become prevalent in cities and urban areas. They have the potential to drastically reduce traffic congestion, lower emissions, and make mobility more accessible. As these services become more commonplace, they will challenge traditional car ownership models - people will question whether they need to own a personal vehicle if they can summon a driverless one in minutes.

For legacy automakers, the rise of robotaxis is both an opportunity and a wake-up call. It's not enough to just build great cars; manufacturers must evolve into providers of mobility solutions. Strategic partnerships and technology investments will be crucial. Those who view autonomy and ride-sharing purely as threats risk being left behind.

As for autonomous driving technology, it's been discussed for a long time, but progress is accelerating. It's not just about cars driving themselves - it's about transforming the entire ecosystem of mobility, from how vehicles are designed, to how they're shared, and ultimately, how we perceive travel. The real power lies in combining electrification with autonomy to create cleaner, more efficient transport networks that fundamentally shift how we plan our cities and move around them.

We're witnessing the dawn of a new era where software and artificial intelligence are as important to a car’s identity as its engine once was. In the long run, success will hinge on balancing advanced technology with everyday practicality: ensuring that autonomous cars aren't just technically impressive, but also seamlessly integrated into our daily lives.

Photo/AI Generated

On Subsidies and Tariffs: Subsidies Should Not Be a Long-Term Plan, and Tariff Protection Will Only Make Companies Weaker

NBD: Donald Trump previously signed an executive order, directing federal agencies to suspend funding for the electrification of the automotive industry, including support for the construction of electric vehicle charging stations. Trump also wanted to end subsidies and incentives for electric vehicles and raise tariffs on foreign vehicles imported to the U.S. How do you think these policies will impact the global electric vehicle market?

Palmer: It's not just Trump but also the EU has expressed similar views.

On subsidies, I somewhat agree, particularly with Elon Musk around incentives. I believe electric vehicles should wean off subsidies as soon as possible. Automobile manufacturing is entirely about economies of scale— the larger the scale, the lower the costs, and that leads to profits. Musk has achieved scale development in electric vehicles, and he may no longer need subsidies at this point, which I think is the right approach. Chinese electric vehicles have also gained the advantage of scale, while Western car companies have delayed too long, with smaller production volumes and higher cost bases compared to China, where costs have benefited from scale advantages.

Perhaps, in the very short term, some subsidies are necessary to push development, but this should not be a long-term strategy.

As for tariffs, I believe tariff protection is a big mistake. History shows that tariffs can be used as part of strategic negotiations. But using tariffs as a protectionist tool makes industries less competitive, as companies no longer compete with other companies in the global market, nor expand their scale globally. Protected companies would growing weaker over time.

Therefore, my advice to the UK government is we should remain open, negotiate with China, and invite Chinese manufacturers to build factories in the UK.

On China's Electric Vehicles: A well-planned "Overtaking"

NBD: You previously mentioned that Chinese electric vehicle companies have become strong competitors in the global market. Why do you say that?

Palmer: My deepest admiration for China comes from my experience serving on the board of Dongfeng Motor.

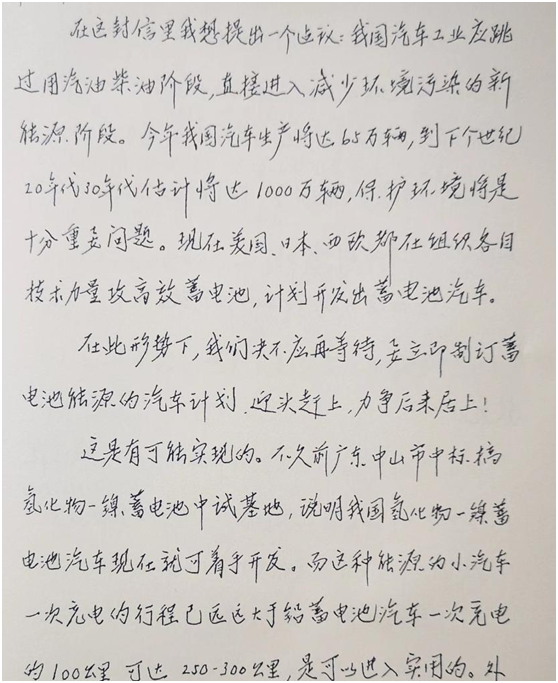

As early as the early 1990s, the Chinese government proposed a strategy to lead the new energy vehicle sector (In 1992, Academician Qian Xuesen suggested skipping the gasoline and diesel stages and directly developing new energy vehicles: to immediately establish an automotive plan for battery energy, to catch up and strive to overtake! In the "Eighth Five-Year" period, a key national science and technology project included "Research on Key Technologies for Electric Vehicles").

I first encountered this vision in 2002 when I joined Dongfeng Motor's board. As the only non-Chinese, non-Japanese board member, I gained a deep understanding of the Chinese government's planning and automotive strategy, which aimed to surpass the West through new energy vehicles.

Through this plan, the first step was to form joint ventures with Western companies, learn how to manufacture cars, bring advanced technology, and build local brands. Then, local brands gradually grew, eventually expanding into exports and globalization.

What impressed me most was that from 1992 to today, China has maintained a consistent understanding of promoting development through industrial strategy, especially in the interaction of the battery industry, steel, and aluminum, and the overall coordinated operation. This process has been like a highly complex and synchronized dance.

NBD: What advice do you have for Chinese electric vehicle companies aiming to win the European market?

Palmer: Build factories in the UK, and this can be explained by historical experience.

In the 1980s, when oil prices spiked, traditional Western car manufacturers were making large cars, while Japanese cars had a technological advantage, producing small, fuel-efficient vehicles. Faced with barriers in the American and European markets, Japanese companies chose to set up factories locally, which is why Toyota became the largest car company in the world.

Strengthening research and learning is the key for China to maintain its momentum in the automotive industry. Not only should companies improve their globalization capabilities, but they should also globalize their production. So, come on, build factories in the UK.

On Tech Companies Entering Car Manufacturing: To Strengthen Luxury Brands

NBD: Chinese tech giants like Xiaomi and Huawei have entered the electric vehicle market. What are your thoughts on this trend?

Palmer: I've been working in the automotive industry for almost 46 years. The car industry was always a narrow field. So if you're an automotive guy, you're an automotive guy, and you become a specialist of automotive, and you might be a specialist in engine or chassis or body, or trim, but basically you are automotive guy.

About 15 years ago, when we were developing the Nissan Leaf, I realized that it was no longer feasible to maintain such a narrow definition. The automotive industry needed to connect with other fields, such as mobile networks, and interact with and be influenced by industries outside of automotive. Back then, I already realized that cars had to change.

Tech companies entering the automotive industry will have a huge impact. But it's very difficult for tech companies to truly become car companies; even Apple and Google failed.

However, Tesla has successfully integrated many industries together, incorporated AI, and to some extent, successfully integrated autonomous driving capabilities. They are trying to experiment with robotaxis.

Also, Huawei's work in this field, particularly in AI integration, is impressive. Both China and the U.S. are at the forefront of AI. The car is an ideal carrier for AI and perhaps the most attractive one.

If traditional car companies and tech companies can cooperate quickly, they will create competitive advantages faster.

China has developed rapidly in AI, and in manufacturing, China has strong advantages in both quality and technology. However, I believe there is still room for improvement in China's cars in terms of driving, handling, noise and vibration, and brand management.

Currently, China manufactures many high-quality, cost-effective vehicles, but there is a need to strengthen the development of high-end and luxury brands. NIO's attempts are a starting point. We need more such brands. Low price isn't the only tool; pricing is also a strategy, and this requires a strong brand appeal. This is an area where China should improve.

Photo/Provided to NBD

When I was CEO of Aston Martin, I had many conversations with Chinese companies. They said they could produce 100,000 Aston Martins in China. I told them they didn't understand luxury goods.

We shouldn't produce 100,000, instead we should produce 10,000 because scarcity is important. Scarcity creates desire, desire creates demand, and demand drives prices. That's the basic supply-demand principle in economics. China has become an expert in low-cost, high-volume production, but the car industry should also have a high-cost, low-volume model, which is something Chinese companies must consider.

On Nissan and Honda's Merger: A Mistake, No Much Synergy Between Them

NBD: Previously, Nissan and Honda announced plans to merge, but the latest news shows that negotiations have been called off due to disagreements on key terms such as integration ratios. The two companies have decided to abandon their merger plan. Could you share your perspective on mergers in the automotive industry from a strategic value standpoint?

Palmer: I think the merger between Nissan and Honda could have been a mistake. The two companies are very similar: both are Japanese, share similar brand values, produce similar types of cars, and target similar markets. There’s not much synergy between them, and in the end, they would just cannibalize each other.

They are already in competition, and a merger would result in a "1+1=1" situation. True collaboration should be "1+1=3". In other words, Honda would end up absorbing Nissan, and Nissan would only exist as a brand.

On the other hand, the partnership between Renault and Nissan has the potential for "1+1=2" or even "2.5", because they are different types of companies serving different markets. Renault dominates Europe, while Nissan is stronger in China and the U.S. So, there is synergy there.

If an automotive company partners with a tech company, like the potential collaboration between Tencent and Nissan, "1+1" could equal 3. There are risks involved; cultural differences could destroy the partnership, but it could also yield huge rewards.

I believe this kind of partnership will ultimately be more beneficial for the industry. In contrast, merging two very similar companies is more of a defensive move.

Photo/VCG

Looking to the Future: 20 Years from Now, Only 20 Carmakers Will Survive

NBD: Looking ahead to the next decade, what progress do you expect in electric vehicles? Which companies or sectors will shape the electric vehicle market?

Palmer: In the early 2000s, there were 20 major car companies worldwide. Today, many new carmakers have emerged. But in 20 years, only about 20 companies will remain. I think Tesla will still exist in 20 years, and we may still see companies like Geely and NIO.

On the technology side, battery technology will see significant advancements. I see two particularly promising paths: one is achieving high energy density through solid-state batteries, exploring the transition from NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) to semi-solid-state batteries.

The other is low-cost technologies, possibly involving LFP (lithium iron phosphate) derivatives or sodium-ion technology. These two paths can be combined with advances in battery cooling and electronic control, which will be very exciting.

There are many debates about the future technological paths in the automotive industry, especially in certain areas.

Although electric vehicles have advantages thermodynamically, it's still unclear whether they will be the absolute winner in all areas.

In some sectors, synthetic fuels still have a place. I believe car manufacturers should fully push electric vehicle development while keeping an open mind to explore the potential applications of hydrogen combustion, synthetic fuels, and fuel cell technology in luxury cars, trucks, and vans.

Note: The order and phrasing of the interview have been adjusted for readability in this article.

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号