Photo/Yu Ruijun (NBD)

On Tuesday, March 19th (Beijing time), the Bank of Japan announced that it would raise interest rates by 10 basis points, adjusting the policy rate from -0.1% to 0~0.1%. This is the first time the bank has raised interest rates since 2007, and it is in line with market expectations. This marks the official end of the Bank of Japan's negative interest rate policy, which has been in place for eight years.

In the past few years, the Bank of Japan has been the only central bank in the world to maintain a negative interest rate. This rate hike marks the official end of the era of negative interest rates around the world.

What impact will this decision by the Bank of Japan have on the market?

Some brokerage firms believe that ending negative interest rates will have a limited impact on the Japanese stock market. From a historical perspective, the Japanese stock market is more affected by the US stock market. As for the impact on the yen, Takahiro Sekido, chief Japanese strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group and former head of macro stress testing at the Bank of Japan, told NBD, "The JPY depreciation is expected to be deterred. More surplus funds from overseas will be converted into JPY. The household sector will use G10 surplus funds not only for overseas investments but also for domestic JPY-denominated investments."

At the same time, Takahiro Sekido emphasized to NBD, that "quantitative monetary easing will continue."

What is the next step for the Bank of Japan after exiting negative interest rates? Tomohiro Ota, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs (Japan), pointed out in an email comment to NBD, "We believe that the Bank of Japan will gradually raise the policy rate after confirming further evidence of sustainable inflation around 2%, and will raise the rate again by 25 basis points in October 2025."

The History of Negative Interest Rate Policy

On March 19th, the Bank of Japan announced that it would raise interest rates by 10 basis points, the first time in 17 years, and end the yield curve control (YCC) policy. (Note: The YCC policy aims to push the yields of Japanese government bonds with certain maturities to the target level by purchasing bonds, thereby driving down lending rates and stimulating economic growth.)

This marks the official end of the Bank of Japan's negative interest rate policy, which has been in place for eight years. This also means that there are no more negative interest rates in the world.

The Bank of Japan's so-called negative interest rate applies a -0.1% interest rate to some funds in financial institutions' reserve accounts. In other words, this interest rate is between the Bank of Japan and commercial banks, and it has no direct relationship with individual depositors. It does not mean that depositors have to "pay the bank money" to save money in the bank.

The policy in question dates back to the economic bubble of the 1980s. At that time, Japan, like a ship swaying in the tumultuous ocean, went through a period of economic stagnation due to the appreciation of the yen following the Plaza Accord in September 1985. This was compounded by four major monetary policy errors by the Bank of Japan in 1989, followed by land financing regulations. These factors like needles, bursting the economic bubble.

By the end of 1989, stock prices in Japan began to plummet, with a decline of over 40%, causing massive losses for banks, corporations, and securities companies, and the the real estate market. As the non-performing loans secured by land came to light, the Japanese financial sector suffered a severe blow. Japan entered a “lost decade” that stretched nearly 30 years. By March 1992, the Nikkei Stock Average had halved from its historical peak in 1989.

Photo/Federal Reserve Bank Of St. Louis

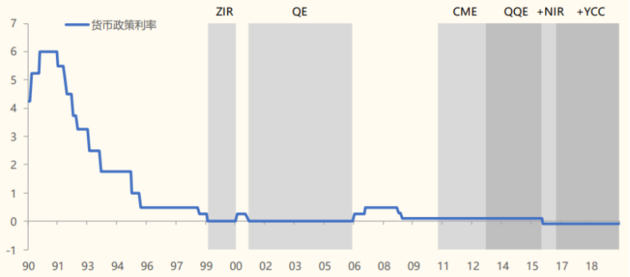

During a prolonged period of deflation, Japan grappled with a stagnant economy, volatile financial markets, and escalating bad debt issues. The Bank of Japan’s six governors—Yasushi Mieno, Yasuo Matsushita, Masaru Hayami, Toshihiko Fukui, Masaaki Shirakawa, and Haruhiko Kuroda—enacted a series of expansionary monetary policies to stimulate economic recovery and combat deflation. These policies unfolded in roughly eight stages.

The Bank of Japan’s unprecedented easing cycle peaked after Shinzo Abe’s re-election as Prime Minister at the end of 2012. As part of “Abenomics,” the bank intensified its easing efforts, introducing Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE), negative interest rates, and Yield Curve Control (YCC). The negative interest rate policy, launched in January 2016, aimed to fight deflation, spur economic growth, and address greater uncertainties in the global market.

Despite Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s willingness to lower negative interest rates further if necessary, strong opposition from the Japanese public, banks with squeezed profit margins, and pension funds and insurance companies seeking higher yields abroad prevented further rate cuts.

By September 2016, the Bank of Japan’s combination of “QQE + negative interest rate policy + YCC” was fully implemented, aiming to maintain reasonable low-interest rates to achieve inflation targets and lessen the adverse effects on financial intermediation.

Photo/Bank of Japan & Sinolink Securities Research Institute

What impact has the negative interest rate policy had on Japan?

The Bank of Japan believes that its Yield Curve Control (YCC) and Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) frameworks, along with the negative interest rate policy, have played their roles effectively.

However, the Bank of Japan has not provided much guidance. It has stated that it will continue to monitor developments in the financial and foreign exchange markets and their impact on Japan’s economic activity and prices. The previous commitment to “take further easing measures without hesitation if necessary” has been removed.

The question of what impact the negative interest rate policy, or the ultra-loose policy that has been in place for eight years, has had on the Japanese economy is a central topic of discussion among market participants and academics. Economists have differing opinions on this.

Observers with a positive view believe that the Bank of Japan’s series of monetary policy tools tried and combined during the deflationary period played a key role in helping to restore the credit market and combat deflation. In times of crisis, monetary policy actions need to be boldly innovative, as the cost of trial and error is lower than in times of prosperity. Takahiro Sekido, Chief Japan Strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group and former head of macro stress testing at the Bank of Japan, pointed out in an interview with NBD that the BOJ's negative interest rate policy contributed to dispelling deflation. Extreme monetary easing and negative interest rate policy were necessary to shift the norm of sticky deflation.

Arata Oto, a Japanese market economist and macro strategist at Crédit Agricole Securities (Asia), believes that the negative interest rates and YCC framework have allowed the Bank of Japan to keep Japanese yields low since 2016. He pointed out to NBD that the central bank committing to an accommodative policy stance led to an upswing in Japan’s credit cycle, as confirmed by the BoJ Tankan survey. The upswing in credit is likely helping to support the pickup in capex activities and the tightness in the labor market. The BoJ’s accommodative monetary policy stance was likely a necessary condition for the economy to exit from deflation but not a sufficient condition.

On the other hand, the negative view on the significance of the Bank of Japan’s ultra-loose monetary policy is mainly based on Keynes’s “liquidity trap” theory and the “balance sheet recession” theory proposed by Richard Koo, Chief Economist at Nomura Securities.

What impacts it will have on Japanese stock and debt market?

As the Bank of Japan exits its negative interest rate policy and implements its first rate hike in 17 years, what impact will this have on Japan’s stock, bond, and foreign exchange markets?

It's worth noting that as the Bank of Japan raises interest rates for the first time in many years, major central banks around the world, including the Federal Reserve, are expected to begin cutting rates this year.

“The JPY depreciation is expected to be deterred. Importers and consumers are exposed to yen depreciation risk. The corporate sector has abundant G10 surplus funds. More surplus funds from overseas will be converted into JPY. The household sector will use G10 surplus funds not only for overseas investments but also for domestic JPY-denominated investments,” Takahiro Sekido pointed out to NBD.

Huatai Securities believes that the Bank of Japan’s interest rate hike will further narrow the US-Japan interest rate differential, boost the yen, but considering the potential impact of Japan’s rate hike and the US’s rate cut on global liquidity are not comparable, the overall impact of Japan’s rate hike on global asset prices is controllable. At the same time, the rate hike will promote Japan’s growth momentum and market performance to shift from external demand to internal demand.

CICC once again cited the performance of various types of Japanese assets during the only two rounds of Bank of Japan rate hike cycles this century, stating that there was actually no significant impact, and even a depreciation of the yen occurred. The underlying logic, in addition to Japanese assets being more influenced by the global economy and the US, also lies in the limited tightening of the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy.

What’s the next move for the Bank of Japan?

Even though this is the first rate hike by the Bank of Japan in 17 years, economists still expect Japan’s borrowing costs to remain close to zero for a considerable period of time. As Takahiro Sekido pointed out in an interview with NBD, “Although the negative interest rate policy has ended, it doesn’t mean that the Bank of Japan’s monetary easing is over. Both households and firms are borrowing more and more, and a sharp and extreme rise in JPY interest rates would be detrimental..”

Arata Oto told NBD, "In order to stimulate corporate spendings, an accommodative monetary and ficasl policy environment continue to remain necessary for the economy to return to a state where inflation runs in a stable manner."

He explained the deflation and growth stagnation that Japan had previously experienced, “A key reason for Japan’s deflation and stagnating growth is likely due to businesses saving excessively. Since the collapse of the economic bubble of the late 1980s/early 1990s, corporates have become increasingly backward-looking, which led them to strengthen restructuring and debt reduction moves. As a result, the corporate savings rate turned positive and has continued to rise. Over-saving (underspending) by corporates destroyed aggregate demand and strengthened structural deflationary pressures. This structural deflationary pressure on the economy has strengthened which indicates that the economy is not close to completely exiting from deflation. During periods of weak corporate spending capacity, government spending could act as a substitute to offset the negative pressure on aggregate demand.. however, fiscal policy also remained insufficient to pull Japan out of deflation. With the lack of fund demand by the corporate and government sectors, the impact of monetary policy was likely limited. The Covid pandemic likely acted as a catalyst for government spending to pick up and in turn strengthen inflationary pressures despite a lack of corporate spending.”

Regarding the subsequent actions of the Bank of Japan after exiting the negative interest rate, Tomohiro Ota, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs (Japan), pointed out in a comment email sent to NBD, “We believe that the Bank of Japan will gradually raise policy rates after confirming further evidence of sustainable inflation around 2%, and will raise rates again by 25 basis points in October 2025. However, we expect a one-year lag between the second and third rate hikes, mainly because we expect Japan’s core CPI (inflation excluding fresh food and energy) for the 2025 fiscal year to be lower than the current level.”

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号