Jan. 14 (NBD) – The University of Maryland recently disclosed that a 57-year-old suffering from terminal heart disease became first-ever genetically-modified pig heart transplant recipient. The patient is in good conditions, says the most recent report.

Experts deemed this operation as a milestone for xenotransplantation and a new approach to the organ shortage crisis. However, risks including immune rejection and zoonotic infection still exist, and how to make animal organs more compatible with human remains a tough challenge.

National Business Daily (NBD) had George Church, Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, and Arthur Caplan, Director of NYU (New York University) Langone's Division of Medical Ethics here to share some insights on genome editing-based xenotransplantation.

Why pigs are chosen to be the donors

Photo/VCG-111364546113

It's noted that the donor pig was raised by Revivicor, a biotechnology company spun off in 2003 from PPL Therapeutics, the U.K. firm that produced Dolly the sheep, the first mammal cloned from a cell from another animal.

"Pigs are much easier and less expensive to raise," said George Church to NBD.

Organs of genetically-modified pigs have long been one of the focuses of the researches on xenotransplantation. But pigs weren't the first choice for donors from the 1920s to 1990s, when scientists were trying to transplant baboon organs, but failed due to difficulties in breeding, differences in size, zoonotic infection and ethical issues.

At the same time, the physiological similarities between pigs and humans and non-human primates also make pigs a more ideal substitute.

"They now have genetic engineering. CRISPR is being used to modify the animals, so their organs are more likely to work. Better post-transplant immunosuppressive drugs also help," Arthur Caplan told NBD.

How donor pigs are genetically modified

According to the School of Medicine of University of Maryland, there were 10 gene edits made in the donor pig. Three genes—responsible for rapid antibody-mediated rejection of pig organs by humans—were "knocked out"; six human genes responsible for immune acceptance of the pig heart were inserted into the genome; one additional gene in the pig was knocked out to prevent excessive growth of the pig heart tissue.

Church's research team focuses on making pig organs more compatible with human bodies via CRISPR. "We've knocked out all of the endogenous retroviruses (25 to 60, depending on the pig strain) reducing risk of zoonotic infection in the (typically) immuno-suppressed patient," he said. This is exactly one of the most influential achievements made by Church's team and provides a basis for the first transplant of porcine heart into human. The result was firstly published in 2015 in Science. In the later news coverage, Science called it "the most widespread CRISPR editing feat to date."

In addition, Church told NBD genes including GGTA1, CMAH and β4GalNT2 that mediate severe and rapid rejection, major histocompatibility (MHC) genes that lead to slower but still severe rejection in human to human transplants, and genes involved in evading natural killer cells (like HLAE/G) and anti-inflammatory genes (like A20), and in blood complement and clotting cascades, have also been changed.

An alternative for organ shortage?

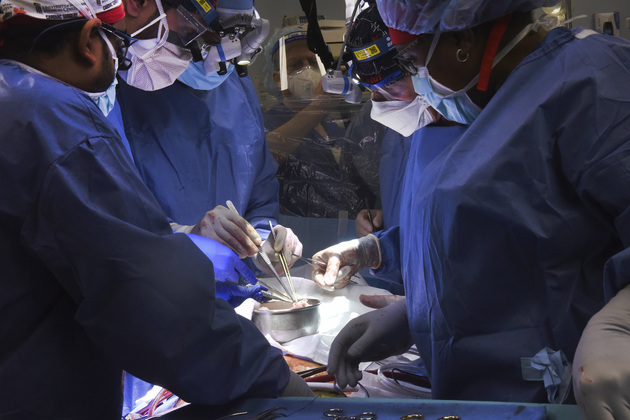

Photo/VCG-111364544501

Organ transplantation stands as the last straw for many patients who suffer from organ failure.

About 110,000 Americans are currently waiting for an organ transplant, and more than 6,000 patients die each year before getting one, according to the U.S federal government website. Therefore xenotransplantation could save thousands of lives if it's proven to work.

In addition to hearts, porcine lungs, kidneys and livers could also potentially be transplanted into humans.

Caplan shared that the pig heart transplant surgery comes hot on the heels of another, in October, when surgeons at NYU Langone Health transplanted an edited pig kidney into a mechanically supported, recently deceased human body that had been altruistically gifted by the family. The research showed that, in principle, such organs can be accepted by human recipients.

When asked about the prospect of xenotransplantation with the help of genome editing, Church said, "Resistance to pathogens, senescence, freezing and cancer have been seen in animals already and these will be refined in the pig xenotransplantation system."

But he emphasized simultaneously that not the pigs are already resistant to a variety of human-specific pathogens like HIV, polio, syphilis, etc.

A long way to go

Xenotransplantation could be a solution but does carry a unique set of risks. "Severe immune rejection may be reduced by engineering the pig, but that remains uncertain. It (pig heart) will still be rejected after a few weeks and (zoonotic) infection will occur," alerted by Caplan.

In fact, pig heart valves have long been successfully used in human bodies. How is the rejection prevented in this case? Caplan explained to NBD, "Pig valves have very little blood in them, and they are mainly cartilage with no immune reaction to them."

"So far, pig valves are not alive (like leather) and need to be replaced (e.g. as a child valve recipient grows)." Church added.

At the same time, the above two professors both agreed the possibility that pig heart will fade more rapidly than the recipient exists in principle, due to different life spans. "But some of that is mitigated by the age and species of the recipient. Also, in my academic lab, we are working on extending life in dogs and humans, and this should be applicable to pig organ donors too," said Church.

Nevertheless, there's still a long way to go.

Email: lansuying@nbd.com.cn

川公网安备 51019002001991号

川公网安备 51019002001991号